Choosing a Helmet

Taking a look at the virginia tech whitewater helmet safety ratings

Editor's Note: This article was originally to be published last year but was delayed due to Helene.

I was online a while back when my newsfeed algorithm posted an article about safety ratings for whitewater helmets. The click-bait worked, and I followed the link to read testing data about one of our most important pieces of safety gear. Little did I know I’d be opening such a Pandora’s Box! The article I read was about the results from a Virginia Tech study first published in the Annals of Biomedical Engineering in October of 2022, rating different brands of whitewater helmets… and the response from the brands that didn’t fare so well on the Virgina Tech tests.

Spoiler Alert: Sweet Protection walked away with the 5-star ratings.

If you want some nitty-gritty, nerdy, numbery details… read on.

On the surface, testing and determining which helmets perform the best in a whitewater environment seems like a straightforward task. Not so much! There actually is no “standard” testing in the USA for whitewater helmets. There isn’t even really consensus about what forces a helmet should be able to withstand, how the force should be dissipated, or even what impacts are likely to produce a concussion. We have to go deeper into the rabbit hole.

The CDC defines concussion as:

… a type of traumatic brain injury—or TBI—caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head or by a hit to the body that causes the head and brain to move rapidly back and forth. This sudden movement can cause the brain to bounce around or twist in the skull, creating chemical changes in the brain and sometimes stretching and damaging brain cells. (www.cdc.gov/headsup/basics/concussion_whatis.html)

What’s interesting about this definition, and many other definitions I found online, is that there are no numbers. It doesn’t define how hard the blow must be, how rapidly the head must move, or what exactly “back and forth” means.

The European standard EN 1385, used by some helmet manufacturers as a minimum to meet or exceed, is that the helmet must tolerate a force of no more than 15 Joules without losing structural integrity. They measured this by dropping a helmet with a 4kg metal head inside, from a 1-meter height onto an anvil and measuring the forces generated with accelerometers. The standard also includes consideration for durability of the outfitting to normal wear, corrosion resistance, “fit” of the fastening system, etc.

Virginia Tech studied 5 different brands of whitewater helmets. They took each helmet, filled it with a mannequin head and a bunch of accelerometers, and hit them with a weighted pendulum. The resulting force was 72 Joules.

Testers from Virgina Tech used a STAR rating system. That’s not a random assignment of constellations based on user opinions or other subjective feedback. The STAR rating system is based on a calculation developed to predict what kinds of head trauma football players might sustain during a game, and subsequent concussions. The calculated STAR ratings were then translated to a more user-friendly 1-5 number of “stars,” with 5 stars being the best and 1 star the worst. In their testing, the helmets were ranked against an average performance and then rated against each other for their discrete 1 to 5- star score.

But what does that mean to us as paddlers? Should we worry about 15 Joules, or is 72 Joules right? Does 15 Joules of force create a concussion? Does 72 Joules create unconsciousness? Would either fracture the skull?

The world of biology tells us this.

Everybody’s brain is different. Your risk of ending up with a concussion after sustaining head trauma is different from anyone else’s. Concussions are diagnosed after the fact. If you have a head trauma and display the signs and symptoms of a concussion, you were in fact concussed. Some symptoms may include dizziness, headache, ringing in the ears, nausea, vomiting, confusion, “seeing stars”, amnesia, slurred speech, or disorientation.

Some research seems to suggest that the absolute amount of force is not the determining factor in concussion. Speed, rotation, and other factors also come into play.

I suspect that there are other important internal factors as well, such as neural tissue elasticity, that are largely determined by a litany of lifestyle choices that far precede any blow to the head. I didn’t find any research about strategies to reduce concussion pre-trauma. After the fact though some early research suggests cigarette smoking can increase the symptoms of a concussion. Paradoxically, injury to a specific area of the brain, the insula, might cure cigarette addiction. This level of complexity in helmet choice is beyond the scope of this article, but look for my upcoming, “Which helmets leave insula vulnerable to injury; 5-star choice for smokers.”

Basically, any strong blow to the head has a potential to cause a concussion.

For numbers' people like me, that’s a VERY unsatisfying answer. It is also remarkably not useful for making decisions about risk mitigation on the river. And all helmets are not created equal, even within a manufacturer.

While it’s theoretically possible to know how much force your head hit a rock with while you were setting up for your combat roll above Killer Fang Falls, it is at the same time unknowable. There is no way to precisely calculate all the variables from head trauma at the point of impact in the natural world. The environment we choose to interact with is too fluid (pun intended) and dynamic.

We can do some hypothetical guess-timations though. Let’s consider a male with an average sized head (setting aside however unlikely it might be that a whitewater paddler would not have a “big head”), who capsizes his kayak in swift water and hits his head on a rock. Doing some rough calculations, the impact to his head after falling a half a meter would produce a moment of something like 9 G's of force. Embedded in that list of mathematical assumptions is that the head would be traveling with almost 9 Joules of energy.

That amount of force applied to the head, happily encased in a well-designed whitewater helmet is below the EN 1385 testing threshold of 15 Joules and is FAR below the 72 Joule forces used in the Virginia Tech study.

Where does that leave us as we emerge from the theoretical world and find ourselves in the real world ready to throw down some cash on a new helmet for the upcoming paddling season? Risk mitigation is as much art as science and always involves a personal line in the sand for risk tolerance. In outdoor activities, when injury and disability can mean long delays for advanced care and rescue, I think being more prepared for the worst is better than being minimally prepared. Whitewater is an inherently risky environment, and we accept that every time we put on the river. As far as helmets are concerned, I’m gonna choose one that is comfortable, durable, and performs the best in scientific testing.

I’ll be ordering my Sweet Protection Wanderer II today.

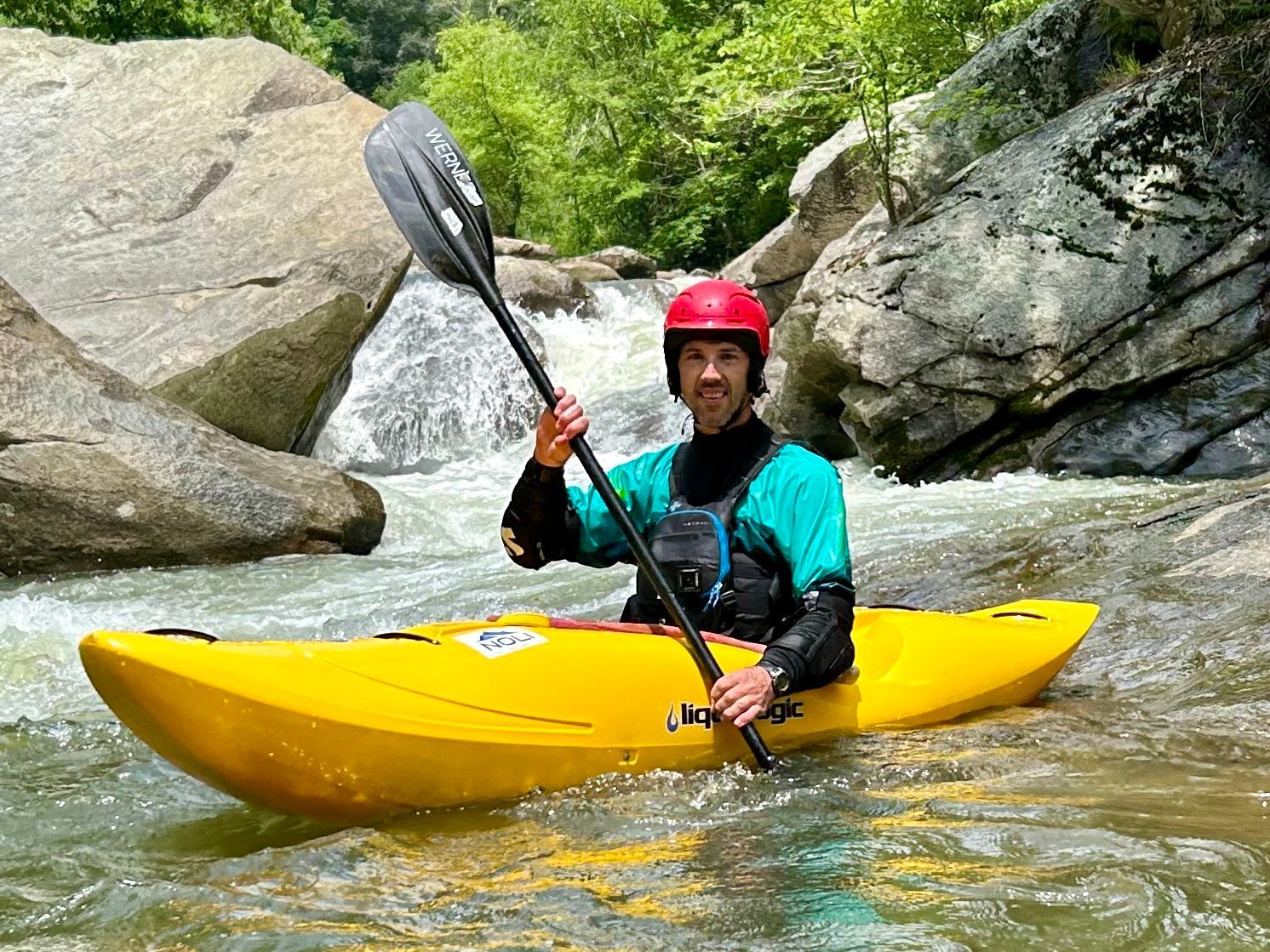

NOLI offers a range of paddling, swiftwater rescue and wilderness medicine classes geared towards helping paddlers safely and confidently enjoy their time on the water. To learn more about these classes and many others, go to

https://www.nolilearn.org.