Survival 101: 5 Ways to Stay Out of Trouble in the Outdoors

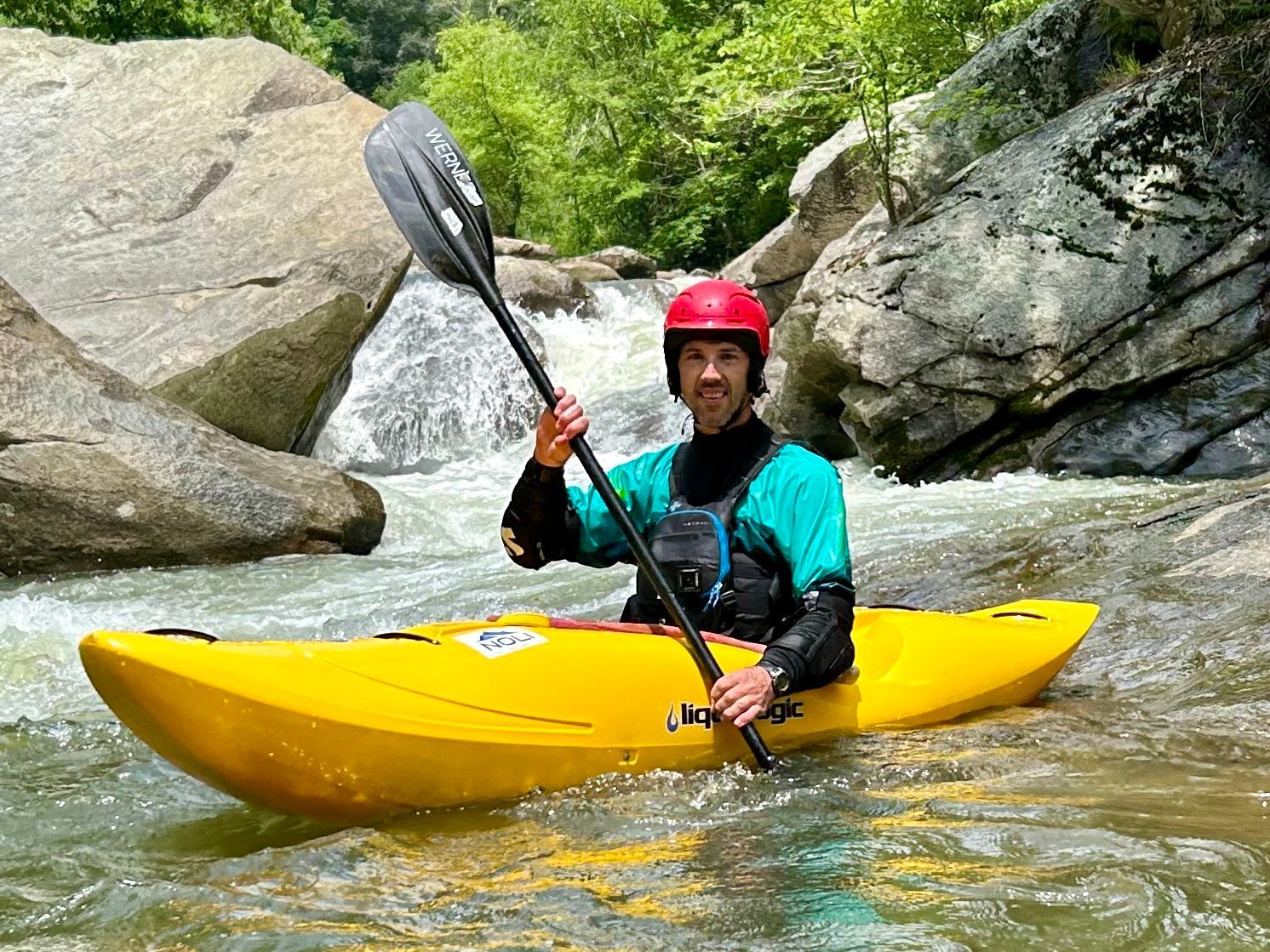

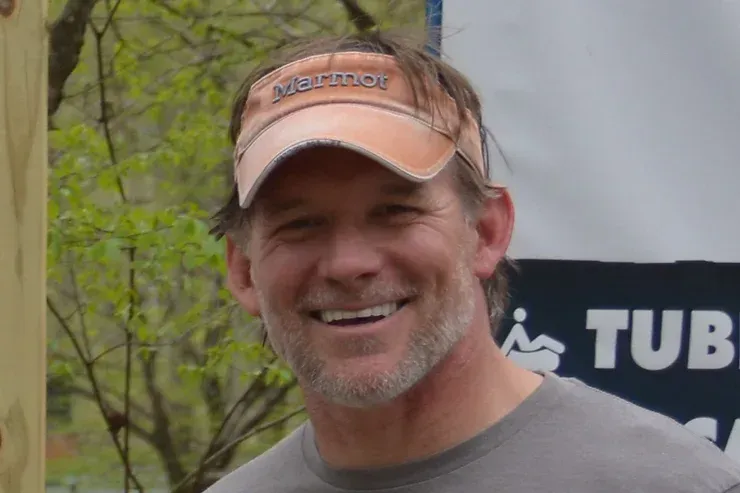

NOLI Survival Instructor Scott Fisher discusses common causes of survival situations and ways to avoid them.

No one has ever embarked on an outdoor excursion, whether to a local trail or a remote backcountry destination, and said to themselves “This is the day I will have an accident or get lost and need to survive.” Why would they? It’s just another day spent outside. They’ve hiked or biked that trail a hundred times. Or kayaked that river for the last decade. Or maybe it’s a new area they are excited to check out that a friend told them about or that they found on All Trails. Others have done it and things worked out just fine. In fact, the online reviews are emphatic: it’s wonderful!

Why then do so many unfortunate souls find themselves in just such a predicament every year, lost, injured, cold, or worse, where their well-being and very survival is at stake? In this ongoing Wilderness Skills series, we are taking a look at what wilderness survival is and how we can take care of ourselves in the outdoors in such a manner that we return home safely at the end of the day. Today, we look at leading causes of survival situations in the wild and ways we can avoid them. Their order is somewhat debated but these 5 causes are implicated in a significant number of outdoor-related fatalities or injuries, in no particular order.

- Hypothermia. Often cited as one of the leading causes of outdoor fatalities and close calls, hypothermia, or when the body loses heat faster than it can create it, is no joke. The human body needs several things to survive: air, heat, water and food. Whereas we can typically survive days without water and weeks without food, we may only last hours in cold conditions if we are not dressed or protected appropriately. In fact, most people are surprised to learn that exposure to temperature in the 50s is enough to eventually cause hypothermia if we do not have adequate clothing and/or shelter. Add in rain and wind and we lose heat even faster. How to avoid it? Wear synthetic or wool layers suitable for the current and forecasted conditions, carry rain protection, carry an emergency shelter such as a mylar space blanket and carry a lighter or matches.

- Dehydration. Another leading cause of outdoor trouble is dehydration. Dehydration occurs when we lose more fluid than we take in and the body no longer has enough water to carry out its normal functions. We think of becoming dehydrated during the warm months but dehydration can occur any time of year, even in the middle of winter. In fact, staying properly hydrated is necessary for our body’s heating mechanisms to function properly so in cold temperatures it’s important that we drink, even if we don’t feel thirsty. Staying properly hydrated will also help us think more clearly and avoid costly mistakes. How to avoid it? Carry one liter of water for every 2-3 hours of hiking or outdoor activity, more as the heat and/or activity intensity increases. Your pee should be clear or no darker than the color of straw. If out longer, carry a means to treat water from natural sources such as a filter or chemical tablets/drops such as chlorine dioxide. Avoid high intensity activities in the hottest part of the day as circumstances warrant.

- Trauma. Lacerations, breaks and other forms of trauma, frequently the result of falls, consistently rank among the top causes of outdoor mishaps. And not necessarily big falls from rock climbing or other high elevation activities. As often as not, they occur while walking or biking on a trail when we lose our balance, fall and injure ourselves. One of our instructors and his wife were hiking to a waterfall on the Elk River in North Carolina when she rolled her ankle. She heard a snap and immediately knew it was broken. These sorts of accidents can be problematic anytime they occur but especially when we are removed from advanced medical care, transportation, warmth and other luxuries that we often take for granted. Add hypothermia, dehydration and/or no easy way to make your way to safety, and what would have been an unfortunate but easily manageable injury in town can quicky escalate to a potentially fatal situation in the wild. Fortunately, the instructor in this case taught wilderness first aid and was able to improvise a splint and, with the help of a friend, carry his wife out. How to avoid it? Make sure the activity and location are appropriate for your experience and fitness level. Wear hiking shoes with a good tread, watch your footing, allow yourself enough time to complete the activity without feeling rushed, take wilderness first aid and CPR training, leave a trip plan with someone so they know where you are and when you expect to return, and carry a communication device (cell phone if you know you’ll have a signal or personal locator beacon such as a Garmin inReach if you won’t) to contact help in the case of an emergency.

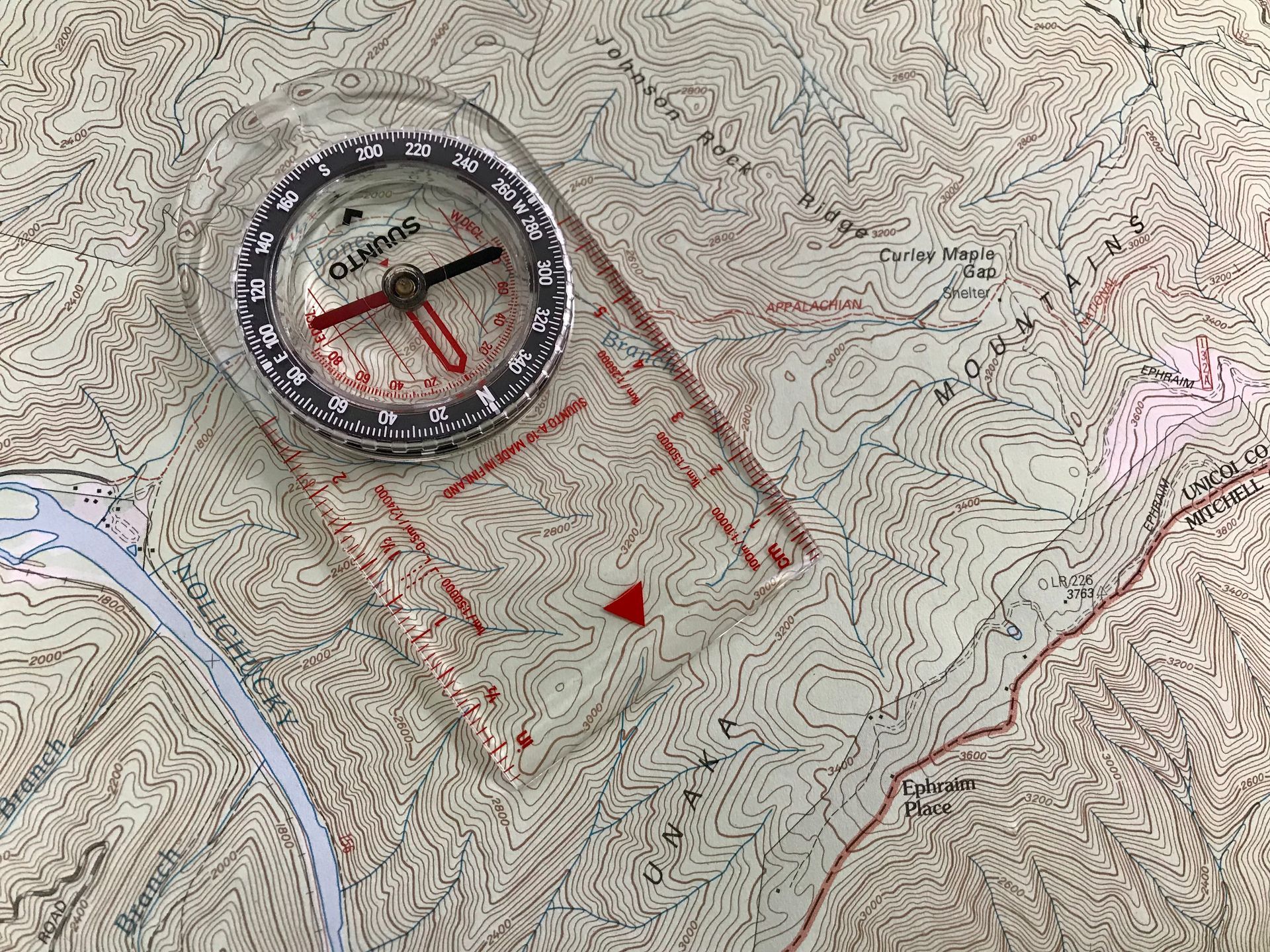

- Lost. If you’ve ever been lost, even for a brief period of time, you likely experienced the sort of dread that can only be characterized as primal. There is something viscerally unsettling about not recognizing your surroundings and having no clear idea how to make your way to safety. It often starts innocently enough; a hiker leaves the trail to go to the bathroom. Or they go off trail “momentarily” to take a “shortcut”. Before they know it, they have lost their bearings and move from place to place, becoming more hopelessly lost with every step. They never planned to spend the night, let alone days, lost in the woods so are woefully unprepared to survive cold temperatures, a lack of water, food, etc. These are the folks who the news reports as missing every year only to, sadly, be found deceased days, weeks or months later, sometimes within a mile or two of their trail. How to avoid it? Carry a map of the area you’ll be in and know how to use it (or use an app like Gaia or All Trails, just make sure you maintain enough battery life). Stay on the trail. This is a big one. Unless you’re experienced with wilderness navigation, resist the temptation to go off-trail or take “short cuts”. If you do have to go off-trail to use the bathroom or find water, mark your location with something visible from a distance, shoot a compass bearing as you leave the trail and count the number of steps you take. When finished, reverse the bearing by adding/subtracting 180 degrees and walk the same number of steps back. This will put you within vicinity of where you left. If you’re still on trail but don’t know exactly where you are, again, stay on the trail. If needed, retrace your steps to the last point you recognize and pick back up from there. If you still can’t get your bearings, consider sheltering in place and await help, assuming you are prepared for the conditions and left a trip plan with someone who knows where to send help to look for you.

- Panic. A well-known outdoor magazine did an article some years ago implicating panic as the leading indirect cause of outdoor-related fatalities. Why indirect? Panic itself won’t kill you but it certainly will exacerbate other causes and contributing factors. If you’re running out of daylight and are uneasy with the prospect of being stuck in the woods at night, for example, you may speed up your pace and inadvertently twist an ankle or fall, injuring yourself in the process. Or you may take a ”shortcut”, only to find yourself lost off trail as darkness closes in. Panic leads to poor decision making and rash behavior and is the enemy of what we refer to as Positive Mental Attitude, or PMA. How to avoid it? Use the acronym STOP. S stands for Stop - remove yourself from any immediate danger, commit to your survival and staying calm, take a seat for a moment, make yourself as physically comfortable as possible, drink some water, and BREATHE. T stands for Think – think through your situation and what you need to get out of trouble. O stands for Observe – see what resources you have to help your situation; look at the map, sky and recognizable terrain features to get your bearing. P is for Plan – make a plan factoring in your current condition, resources, daylight and weather; self-evacuate or shelter in place and await assistance.

We cover these topics and more during our wilderness survival and navigation classes at the Nolichucky Outdoor Learning Institute (NOLI). Learning these skills helps ensure we can confidently head out into the wilderness or to our local trail and return home safely. They can help us survive an emergency through competent and timely action. And, maybe best of all, learning these skills is fun!

Want to learn these valuable skills? Join us for one of our upcoming wilderness survival and navigation classes.

See you outdoors!

Scott Fisher is the founder and executive director of the Nolichucky Outdoor Learning Institute. He teaches wilderness survival, wilderness navigation, whitewater kayaking, swiftwater rescue and Leave No Trace.