Kayak Safety & Rescue: Life Lessons in Haro Strait

It was a nearly perfect morning on the Washington state Pacific coast. My wife (Michelle) and I had a delicious breakfast, broke down camp, loaded our rented tandem kayak, and paddled down the sheltered bay that bisects Stewart Island. Along with our guide, Annie, we ran with the tide and a light southwesterly breeze to make the three-mile open water crossing to Henry Island. As we crossed in the 2-foot swells, we were just cruising, enjoying the warmth of the sun, and gazing toward the horizon hoping for our first orca sighting of the trip.

Once we passed west of the tip of Henry Island, we headed south a bit and our guide signaled that we would take a break in a field of bull kelp. Thickets of bull kelp make an ideal resting place for sea kayakers because the kelp floats, which are round and 3 to 8 inches across, protrude from the water and break up the momentum of the waves. We stopped for a few minutes, bobbing up and down with the swell, occasionally chatting but mostly taking sips from our water bottles. Over the sound of waves and calling birds, Michelle heard a distant noise. It sounded like a cry for help – or was it a gull? We listened for a few seconds when another, more distinct yell rang out. For an instant we all hesitated, trying to determine the direction of the cries. From our vantage point low to the water, all we could see was dark bull kelp floats scattered across the ocean’s surface. It sounded like the panicked calls were coming from somewhere between us and the shoreline, so we sprinted southeast through the kelp patch toward shore. After we broke through the offshore kelp forest, we spotted two small dark objects on the surface alongside something that looked like a partially submerged log. As the distance closed, the larger object resolved into a flooded green aluminum canoe. The smaller ones were two middle school age boys struggling to reenter the water-filled boat. Every time they tried to enter; the boat would flip. As we neared, they quit trying to enter their boat. Instead, they hung onto the hull of the now inverted canoe and stared quietly as we approached.

Michelle and I coasted up on the right side, leaving about a 5-foot gap between our tandem and the canoe, just in case the boys panicked and tried to climb on the deck of our boat before we were prepared. Caution is necessary in a situation like this because a panicking victim can easily capsize a would-be rescuer’s boat - leaving more people in the water. Annie coasted up a similar distance on the left side of the flooded craft. Our first evaluation was that the boys had been in the water for at least fifteen minutes. They were shivering, minimally responsive, and their movements were clumsy. After quickly weighing the options and their condition, we agreed that we could get them out of the water and warm them up more quickly by towing them to shore than by attempting to get the boys back into their boat. We then instructed the closest victim to grab the left perimeter line behind the rear cockpit of our tandem. At first, he refused because he did not want to release the cell phone in his right hand. The impasse was broken when Annie slid her boat up on his left side and convinced him to hand the phone to her. The other boy was similarly coaxed to grab the left stern perimeter line of Annie’s boat. We then started toward shore in the direction of the nearest cottage. When we had closed to within 75 yards of the house, a man came out onto the shore, saw us towing the boys, launched a tandem sit on top kayak, and headed out toward us. The boys, who were shaking with cold, were handed life vests and then hauled aboard the sit on top kayak by their father, while we stabilized the boat. As the reunited family headed back toward shore, we recovered the flooded canoe and towed it to shore. After this brief but adrenaline-filled detour, we continued our journey southwards down the Haro Straight, skirting the shore of Henry Island.

This story, with its happy ending, may seem like just a minor anecdote. But those children were exceedingly fortunate that we happened by, heard their cries for help, and responded appropriately. One boy had on a cotton T shirt and shorts and the other just board shorts, which was barely adequate for the air temperature of around 60 degrees. However, a person without protective clothing who is mostly submerged in water loses heat 30 times faster than they would in air of similar temperature. The surface water temperature in Haro Strait is typically about 51ºF at that time of year, and they had been in the water for an unknown period. By the time we intervened, both boys were shaking, uncoordinated, and moderately unresponsive due to hypothermia. So – what can you learn from this story that will help you from getting into a similar situation?

- First, the boys had no life jackets and were not dressed for immersion. Individuals of low body mass who are not wearing either a wet suit or dry suit may be incapacitated or rendered unconscious within 30 minutes after immersion in 50ºF water – a time which may be nearly doubled if the victim is wearing a life jacket. More importantly, once a person without a life vest is rendered unconscious by hypothermia, they will drown. Even in warmer water, a blow to the head, exhaustion from treading water, or hypothermia due to extended immersion are more rapidly deadly for a person who is not wearing a life jacket compared to a person who is. Thus, it is important to wear your life jacket at all times when on the water, as well as when entering and exiting the boat.

- Second, the capsized canoe had no internal flotation and no self-rescue equipment. Even if the boat contained such equipment, it is unlikely that either child had been trained how to reenter a flooded canoe. Therefore, they had no way to get out of the water to reduce their heat loss – nor could they use the canoe to return to shore. Canoes, or kayaks without water-tight internal bulkheads, should have floatation in the form of inflatable float bags or closed-cell foam blocks anchored securely inside the boat. Such flotation raises the boat higher in the water when it is flooded, making it easier to self-rescue. Additionally, minimizing the amount of water that can enter a capsized boat reduces its weight and the free surface effect, making it more stable for assisted rescues and easier for rescuers to empty. In the rescue above, the hundreds of pounds of water in the 18-foot canoe made a modified T rescue nearly impossible, particularly considering the near shore swell and the reduced dexterity and strength of the swimmers. Thus, we made a nearly instantaneous decision to abandon the flooded boat and get the boys to shore.

- Third, one boy initially delayed the rescue by not being willing to relinquish his cell phone. As they likely had only a few moments before becoming completely incapacitated by the cold, any unnecessary delay in getting them out of the water could have had tragic consequences. The bottom line - nothing you own is worth your life.

- Fourth, the conditions were not conducive to the long-term survival of anyone in the water at that location – even if they were wearing a wet suit or dry suit and a life vest. The wind and tide direction would have made it very difficult for even a strong swimmer to swim the 150 yards back to shore. Instead, the boys were being pushed diagonally away from shore by an offshore wind and 3 mile per hour tidal current. Since it was a weekday, there was very little boat traffic and thus, very little chance for immediate rescue by other boaters.

- Fifth, the boys had no effective emergency signaling devices. Though we don’t know whether they tried to contact their parents with their cell phone, phone reception in that location is spotty at best. Without life jackets, their heads were barely above the water’s surface, making them difficult to see from any distance amidst the confused swells and floating bull kelp. We only heard their cries of distress because we were slightly downwind from their location when we stopped for our rest break. The sound of their cries was so faint that we could have easily missed them in the noise of paddle splash had we been still padding, rather than resting. It is also unlikely, because of the wind direction, distance, and background noise, that anyone on shore could hear them. Given their direction of drift in the offshore wind and ebbing tide, they would have been swept southwest into 8-mile wide Haro Strait with no effective way to signal for rescue.

- Because of these, and other factors, this situation could have easily ended with the serious injury or death of these two children.

After reading this, you might think “Well, I don’t paddle in the ocean and so don’t really have to worry about this around here”. So, consider the following fictional scenario based upon the event described above.

It is the end of February in east Tennessee and the weather is unseasonably warm. The warm, sunny weather gives you a bit of cabin fever, so you decide to go out for day paddle on Watauga Lake in your new kayak. It is a blustery day, with the wind out of the southeast about 5 miles per hour. Since the wind is a bit cool, you decide to start your paddle at about 3PM – when the temperature is predicted to hit 75ºF. You decide to paddle out from Watauga Point around Clifford Island and back – a round trip of just under 2 miles. Based on your previous paddle trips, you should easily get back to your car by 4:30 PM. You stick a water bottle, some snacks, and a fleece jacket into the cockpit and put your cell phone and car keys in a dry bag behind your seat. Because you find it uncomfortable, you slide your life vest under the rear deck bungies. Then you set off toward the island, ready to enjoy some solitude and nature on a beautiful late-winter afternoon. As is typical in the afternoon on a warm, late winter day, the crosswind picks up as you paddle across to the island. After stopping occasionally to drink and look at the scenery, you finish circling the island and head back toward your car. When you round the northwest side of the island, you notice the wind is blowing harder and that the channel between the island and Watauga Point is covered with small white caps. Even though the ride is a bit “bouncier” than you are used to, your kayak is stable and you head onward – looking forward to a nice dinner at home. About halfway back, a gust of wind blows your cap off. You lunge to your left to grab your hat, lose your balance and the boat capsizes - dumping you, your fleece jacket and the dry bag containing your keys and cell phone into the lake. The sudden immersion in 45ºF water is incapacitating and it takes a moment for you to get your bearings after you come to the surface. In that moment, the wind pushes the overturned boat just out of your reach. You try to reach the boat to retrieve your life jacket, but the wind and wave action is blowing it to the east faster than you can swim. You look around but there are no other boats in sight. The cold water is chilling you quickly and you must make a choice, swim back to Watauga point or make for the island. You try for Watauga Point but the exertion and convective heat loss lead to hypothermia, muscle cramps, and possibly loss of consciousness – all when you are less than a hundred yards from shore…

Paddling is a wonderful way to get exercise, forge lifelong friendships, and connect with the natural world. I would not trade anything for the experience of watching the sunrise on Watauga Lake or sitting around a campfire with some good friends on a Suwannee River sandbar. Paddling safely reduces the risk of harm to yourself, your family, and to those who might try to rescue you. So how do you paddle safely? Buying a boat with appropriate flotation and safety gear matched to any conditions you might conceivably encounter is a good start. However, the right gear makes little difference if you don’t know when or how to use it properly. More important still is sound judgement – which keeps you from exceeding your skill and experience level and thus putting yourself and others in danger. Such judgement can be developed only by training and experience. No YouTube video or “how to” blog can replace “hands on” instruction on the water from a highly skilled professional. Though such training takes time, effort, practice and patience, I would ask you this – “How much is your life worth?”

If you are interested in becoming a safer and more skillful flatwater paddler, consider taking an upcoming “Flatwater Safety & Rescue for Paddlers” course on July 8 or August 5 offered by the Nolichucky Outdoor Learning Institute. You will be glad you did. To learn more about all the classes NOLI offers, go to www.nolilearn.org.

Have fun on the water and stay safe!

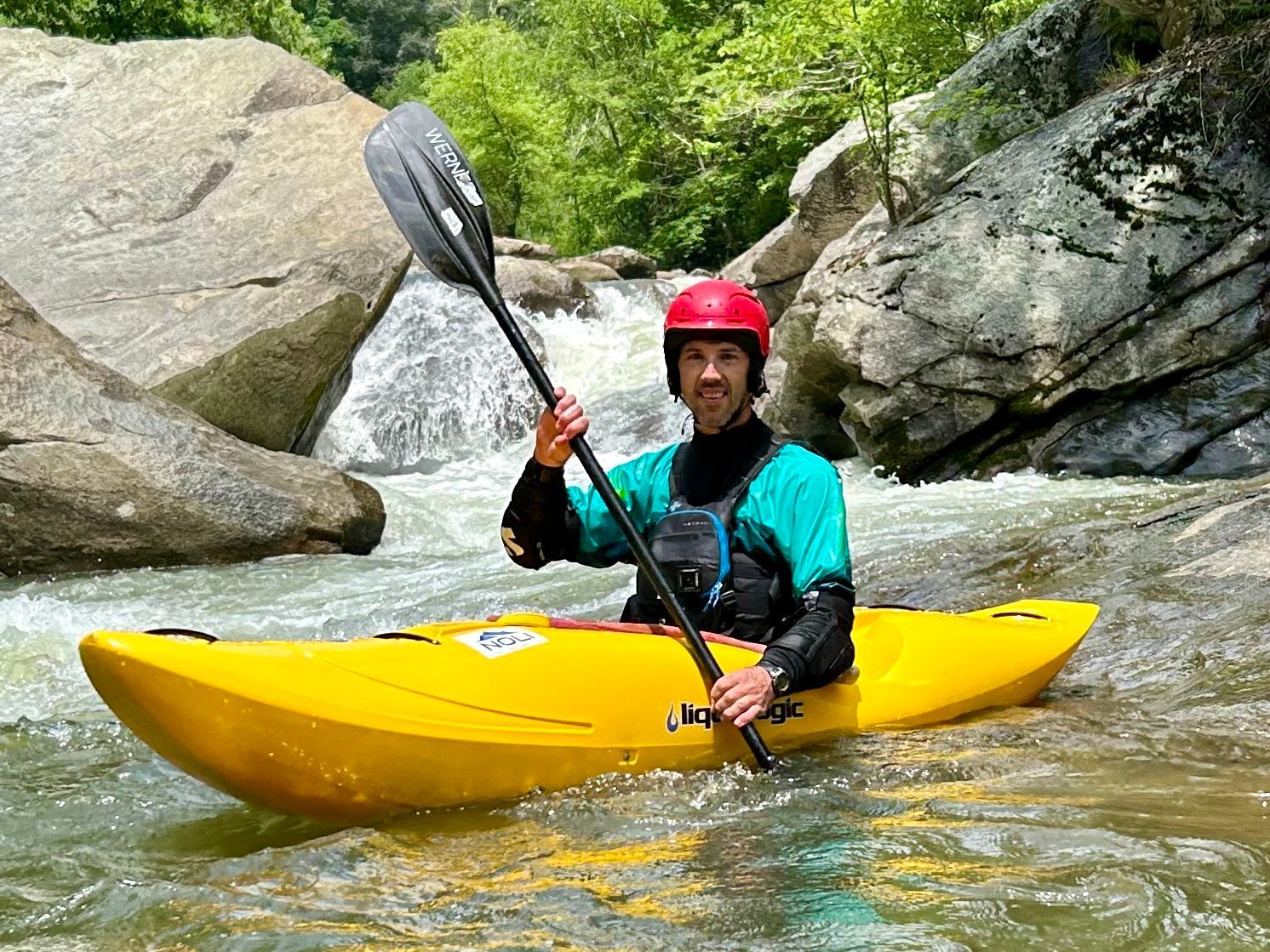

Rob Schoborg is an avid kayaker, guide and outdoor enthusiast and teaches backpacking and hiking classes for NOLI.