Survival 101: Don't Give Up!

In 1971, a 17 year-old girl was flying with her mother on Lansa Flight 508 when it was struck by lightning and disintegrated mid-air, falling 10,000 feet to the jungle floor below. The girl, Juliane Koepcke, had just graduated high school in Peru and she and her mother were flying to meet her father at the jungle outpost where they conducted research as zoologists. Juliane miraculously survived the fall, but had a broken collarbone, a deep gash to her right arm, a concussion and one eye swollen shut. She searched for her mother to no avail and then, remembering advice that her father had given her to follow water downstream to human settlement if ever lost, began her harrowing journey to find her way to help. She spent the next 11 days bushwhacking her way alongside and, sometimes, in rivers battling pain, hunger, fatigue and despair with only the clothes on her back and the vague hope of rescue. Day after day she trudged along with no idea where she was and whether her course was, in fact, leading to civilization. She tried to rest when she could but the onslaught of mosquitoes made it nearly impossible. To make matters worse she soon realized that the wound on her arm had become infested with maggots, which she tried unsuccessfully to dig out with a bobby pin. And yet, despite all that, she kept going. She wanted to get back to her father and refused to give up. She was determined to live.

After 11 days, she came upon a shack along the river with a small boat tied up, next to which was a gas can. Recalling how her father had once poured gasoline on an infested wound on their dog, she doused the gash on her arm and counted more than 30 maggots as they emerged. Exhausted and not wanting to steal someone’s boat, she laid down to rest and was later discovered by some fishermen when they returned. These fishermen transported her by canoe to a village where she was airlifted to a hospital and finally reunited with her father. Juliane was the sole survival of the Lansa Flight 508 disaster and, yet, later evidence at the crash site indicated that others may have also survived the initial crash, only to later perish while waiting for help.

How, then, did a teenage girl with little to no survival training survive such a tragedy while everyone else perished? She certainly did not fit the stereotype of the barrel-chested, brash survivalist with an oversized knife on their hip. No, what Juliane had was better than that. It was quieter and more subtle. What she had was an indomitable will that, paired with that one bit of knowledge from her father to follow water downstream, eventually led her to help and cemented her story as one of the most inspiring accounts of survival over the last 50+ years.

We often discuss Juliane Koepcke during our wilderness survival classes at the Nolichucky Outdoor Learning Institute (NOLI) in Erwin, as a model of both what survival is and is not. We want to dispel the myth upfront that only “tough” guys and gals can make it. Survival isn’t about conventional physical toughness so much as it is about knowledge, skills and, above all else, attitude. For every story like Juliane’s, there are many more that ended in tragedy when otherwise strong and capable outdoors people were unable to muster the inner strength to carry on in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds and just not give up. It’s easy to understand why. Panic, pain, hunger, thirst, exposure, fatigue, loneliness, despair and complacency are all enemies actively working to chip away at our will to survive. They will undo us if we let them. It is a psychological game as much as a physical one and the single most important thing we can do when we are lost or injured miles from help is to commit to our survival early and often. Set goals: “I will see my family again and nothing will keep me from getting back to them.” Even small goals can help us stay on course and moving forward: “I will crawl to that next tree. And the next. And the next.” And so on until we’re rescued or make it to safety. Within the survival community we call that Positive Mental Attitude, or PMA, and it’s the first and most important of the 7 Priorities of Survival.

As crucial as PMA is, we mentioned that knowledge and skills are also hugely beneficial and potentially life-saving when faced with a survival situation. And that’s where the other 6 Priorities of Survival enter in: First Aid, Shelter, Firecraft, Signaling, Water and Food. Knowledge and skills related to these priorities provide the framework to help us ward off those enemies of survival mentioned earlier as well as provide a process to systematically attend to our needs in a productive and proactive manner. There are several things that humans need to survive. These include air, heat, water and food. Do without any one of them for long enough and the human body simply cannot function, causing it to shut down. We refer to these needs and their respective timeframes as the Rule of 3s. We can survive roughly 3 minutes without air, 3 hours from exposure to cold, 3 days without water and 3 weeks without food. These are generalizations, of course, but thinking in these terms informs where and how we should be spending our precious energy.

We cover these skills and more during our wilderness survival classes at NOLI. Not only do we teach the 7 Priorities, we teach additional related skills as well, such as knife use, knots, navigation without the aid of a map and compass and, importantly, how we can prevent most survival situations from happening in the first place. Learning these skills helps ensure we can confidently head out into the wilderness or to our local trail and return home safely. They can help us survive an emergency through competent and timely action. And, maybe best of all, learning these skills is fun!

Want to learn these valuable skills? Join us for our next 2-Day Wilderness Survival Class on Sep 30-Oct 1 https://nolilearn.app.resmarksystems.com/public/short/pZl8XxrTsj. To see all upcoming classes go to www.nolilearn.org.

See you outdoors!

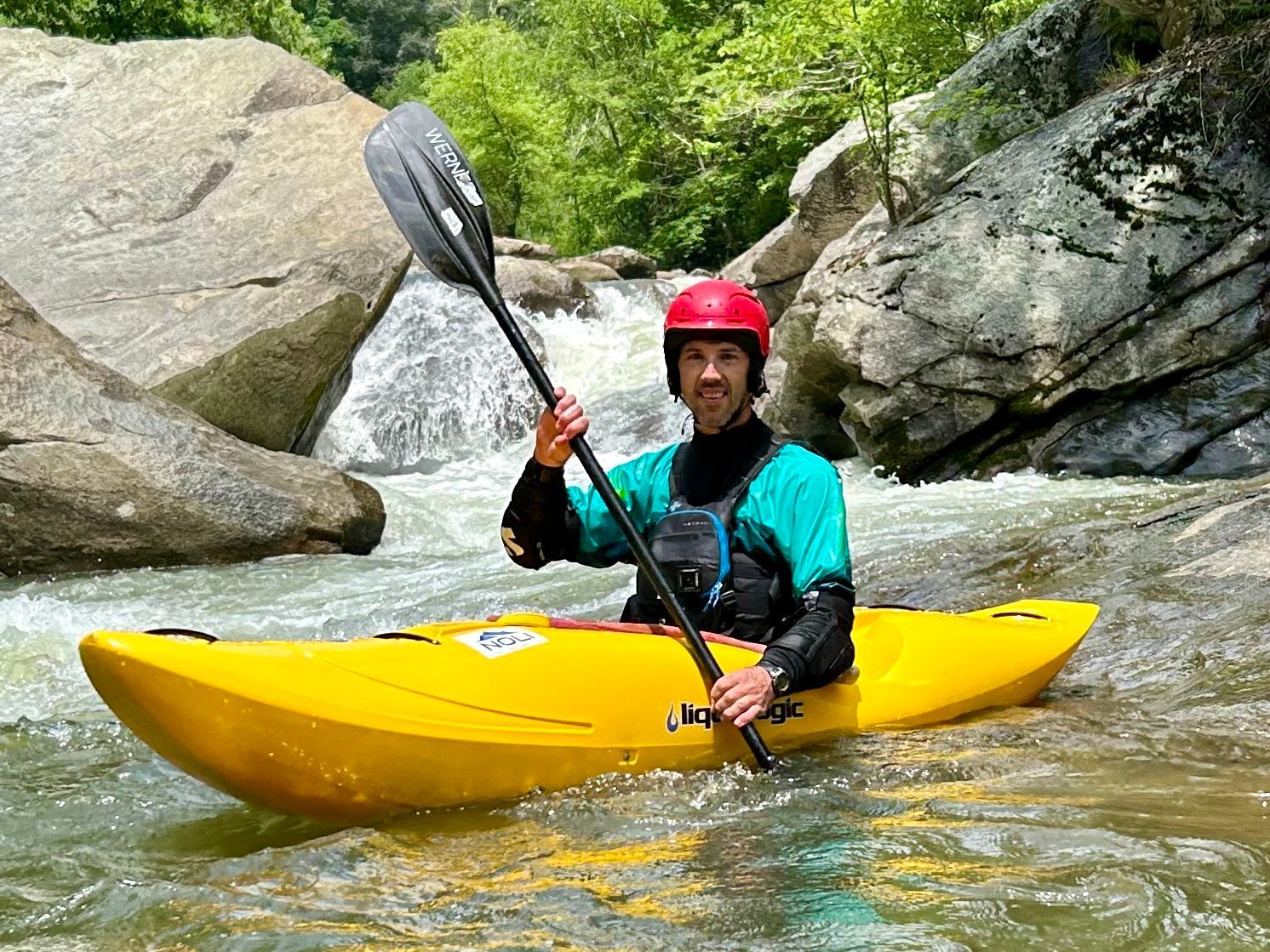

Scott Fisher is the founder of the Nolichucky Outdoor Learning Institute (NOLI) and teaches survival, wilderness navigation, whitewater kayaking, swiftwater rescue and Leave No Trace.